My father took his own life on a Monday evening in late July.

I returned from his funeral last week on a 6 AM flight out of Milwaukee. I watched Girls on the plane and I ate a disgusting airport bagel. Back in the tree-canopied avenues of Brooklyn, I promptly moved apartments before finally settling my head on a pillow for the first time since bidding farewell to my dad.

I escaped into reading when I learned of my father’s death — it became my one true refuge. I read Bret Easton Ellis’ The Shards and then read Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays. From there I devoured Killers of the Flower Moon and then Less Than Zero and then Rent Boy and then The Guest and then, beside the cerulean soundscape of an AirBnB’s pool in Denver (included a drunk bi girl and a painfully-tatted gay guy comparing how “real” the people in their respective lives were), I read Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking.

In the book, which details how Didion lost her husband to a heart attack as her daughter teetered in and out of the emergency room, she poses “the question of self pity.” It’s something I find myself considering as I embark upon almost any social interaction of late. The unsuspecting other party asks “How are you?,” and abruptly I’m faced with an intolerably unfortunate lose-lose scenario: either I say “Fine, thanks” and feel the encompassing squirm of dishonesty and dysphoria blast from my every pore, or I say “Well, my dad just shot himself in the face, so I’m not great,” and the person turns a particular shade of cornflower blue and develops a mixture of: 1) guilt at having broached the subject and 2) reproach at me for having been so forthcoming with such grim tidings. The truth is, I am seeking sympathy when I rattle off this horrific fact — is yearning for some miniscule amount of compassion for my plight so atrocious an act? It’s a question that comes up again as I write these words now — what to maintain privately for myself, for my family… what becomes oversharing, and self-indulgent, and disrespectful of the dead? Yet I can’t help but say something — I’m an external processor, a person who can’t hold things in, who needs to say what I’m feeling in order to fully feel it. Perhaps I will regret recounting this time of my life so frankly when I’m older — in fact, I’m almost sure of it. Yet I don’t see how I could possibly not talk about it.

My father’s funeral took place on a Super Blue Moon, as my little sister Lexi pointed out to me the week prior when we were together beside the AirBnB’s decadent blue-lit pool in Denver visiting my other sister, Winnie.

In the days leading up to the funeral, I would look up at the night sky and see the silvery fixture of Luna beaming down upon me, growing larger every day, thus serving as a countdown clock until the day we would bid my dad adieu. Now, in the days following that funereal Thursday, I look at the sky and watch as the moon records that date becoming more and more distant a memory.

On “Beautiful People, Beautiful Problems,” Lana Del Rey croons that “blue is the planet from the eyes of a turtle dove.” Deep, dark blue was the color of my father’s eyes. Seafoam was the color of the cracked pleather cafe couch I was sitting on when my mom called me to deliver the news. Lapis is the color of the boxer shorts purchased at Dick’s Sporting Goods I wear as I type these words now. Ultramarine was the armor of the dragonfly that landed on my arm in the lake, days after my dad’s death: him visiting me from beyond, I reckon. Sapphire was the name of the senile cat that has lived with me and terrorized me with its yowling and vomited in front of me these past five months.

A periwinkle veil of cloudy late-afternoon light gave Paddy’s Pub, where the funeral took place, an appropriately melancholy air as my wonderful friends and my family and I set up the tablecloths and the flower arrangements around the fittingly weathered, otherworldly Irish bar where we all said our goodbyes to Scott McNeill Dresden. In the narrow stone courtyard a small tiered fountain burbled quietly. A chipped statue of an eagle spread its wings across from the screen where my aunt Heidi set up a projector to play a slideshow of now-tragic memories. A little plaster deer was nestled in a corner between large pots containing ficuses on their way to join my dad in the grave. Up a short set of steps inside was a cramped, charming little pub — I remember the light of it in my head now as a murky red — a wizened old woman, Paddy herself, mixed drinks for us earlybirds and offered her condolences.

At the funeral my speech followed my sister Lexi’s. Hers had left me wracked with sobs, and I choked through the opening line of what I’d planned to say: “My name’s Hilton, I’m the oldest of Scott’s children, and I’m the only one who inherited his hair” (for those of you reading this who somehow arrived at Babbling On without first learning of my visual parallels to a patch of steel wool: I have an extremely curly mop protruding from my scalp). People laughed.

After that I took a deep breath and told stories of my memories with my dad: how he taught me to be strong in my convictions (by making my sister Winnie and I go up to smokers as kids and cough in their faces.) Or how he showed me not to take life too seriously (by helping me stage my death in the backyard using a ripped up T-shirt and ketchup, and then checking my pulse in front of my sister and claiming I’d been killed by a wolf.) He taught me how to take risks, in the Wisconsin Dells (by pushing me down a hundred-foot high waterslide where you needed to weigh at least 120 pounds to be heavy enough not to fly away into the clouds and splat on the concrete — I barely clear that poundage twenty years later, and certainly didn’t then.) He taught me to make the most of what I have — for instance, when he used to take Winnie and I camping at Devil’s Lake, he’d remove the little black bead dangling from his belly button ring and hide it in a lakeside cave. Then he’d tell us we needed to find the “Devil’s Eye,” and that to do so would be significantly cosmic. We’d scour dirty caves for the little black bead until we discovered where it had been mysteriously left for us on some flattish rock, and my dad would subtly return it to his navel, and we’d all carry on with our lives feeling in tune with some higher power.

On my twelfth birthday all I wanted was Kit Kittredge, the American Girl doll who grows up in the Great Depression and wants to be a writer and serves blonde bob. At my dad’s house on that fateful November evening, I got Harry Potter books and Green Bay Packers gear and an All-American Rejects CD, but I didn’t get Kit. And so I went and cried on the stairs and threw a tantrum and served cunt in a bad way. Then my dad pulled out a large box that contained the Marvelous Ms. Kittredge. Of course I’d ruined it by revealing my true colors as a coddled cantankerous killjoy, but I still think back on that moment, draped dramatically across his stairs, when I realized he had, indeed, paid attention to what I’d been wanting, and obliged, however begrudgingly.

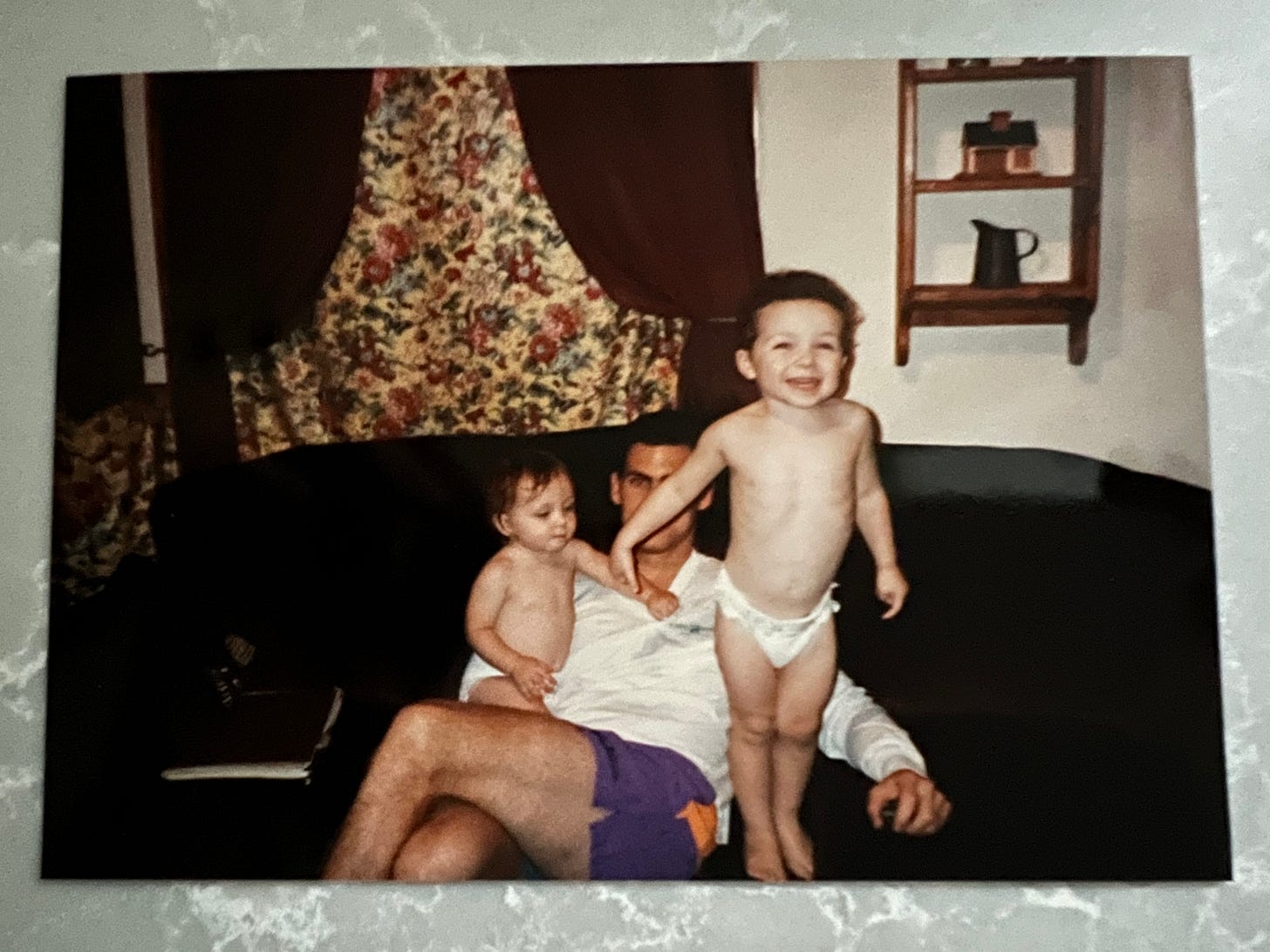

My dad and I had grown apart in the final years of his life — in fact, we’d never gotten along particularly well. But I loved him, and I know he loved me and he was proud of me. I’ll remember driving with him and listening to The Black Eyed Peas’ Elephunk and Monkey Business, and Bob Marley, and how there was always a red tin of Altoids in the little armrest compartment between the driver and passenger seats. I’ll remember how he loved to be outside, and how he took us snowboarding, and tubing, and wakeboarding, and hiking, and biking (and the smell of his farts as we rode behind him on the tandem), and the way he curled his lips back to expose his white teeth when he was chasing us around the Milwaukee Public Library and pretending to be Skeletor as we hid in the little play lighthouse nestled behind the children’s books. I’ll remember the enormous eyeball tattoo he got on his bicep with a rainbow of eyeshadows framing it, purportedly a nod to his support of my LGBTQishness, which he also supported by taking me and my friends to Industry in Hell’s Kitchen, and the now-defunct Therapy bar (not to be confused with actual therapy, which we both sorely needed). I’ll remember him as a party-loving enjoyer of life, a man who placed competitively in Ironman triathlons, a man who was curious about everything and had his nipples pierced and looked dapper in his doctor’s coat. He wore True Religion jeans. He won a bikini contest on a cruise ship wearing a hot pink thong. He got the cops called on an enormous rager he threw for my sister’s second birthday. We had a pug named Buddha, and later another one named Simon. Dad built a bar in our basement called “Buddha’s Bridge End Tap,” and there was a table in it shaped like a martini glass, with a green foam olive that you could take out of the table’s frame and throw at unsuspecting drinkers at the counter.

I feel I have a responsibility to mention what I said at the end of my funeral speech: I don’t believe my dad would have done this in his right mind. After reading my Aunt Heidi’s statement to the police I feel compelled to voice that I think he was coerced into killing himself, and that a full criminal investigation is in order, and that anyone with information regarding the case should please reach out to my family.

There’s a line in Hole’s song “Doll Parts” that gets repeated multiple times, Courtney Love snarling: “Someday you will ache like I ache.” My dad is the first person I have known well (although I hardly did, it seems) to have died. His feels like the first suitcase plucked from the baggage claim of my life, carried out towards the taxis and away from me forever. Somehow in the back of my mind I did think that one day we would reconnect and be part of each other’s existences again as adults. I cannot believe that I’ll never see him again.

I ache with anger at myself, for not reaching out more; at him, for abandoning all of us; at the world, for carrying on as normal in the wake of this horrific tragedy; and at the evil woman who I believe is responsible for his death. I feel a gnawing ache in my body that feels spoken to when Courtney Love sings that line. And I realize with a chill that she’s right, that in one way or another everyone will experience death, someday.

I felt I needed to escape. My words had been said. Thus written and forever memorialized, I wanted to leave behind everything I knew and wake up on an entirely new planet, like Amy Adams does in Enchanted. I’d bought a one-way ticket to Berlin earlier this summer, before this terrible tragedy occurred. Now, the trip feels more crucial for me than ever. I leave tomorrow, and I’ll stay in Berlin for about six weeks. Auf Wiedersehen, loves.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t thank my friends who flew in from out of town for the funeral: Alec, Nick, Talia, Molly, and Rachel. You all mean the world to me and your kindness will imprint itself upon me for the rest of my life. Your presence made all the difference for me and my family. Thank you to my Mom, who should not have to go through this again and is handling the lion’s share of the burden with such grace and warmth it astounds me. Thank you to Winnie — I love you, and I hope you’re having fun in Portugal. Thank you Lexi for pointing all of us toward the signs of his presence around us, and for making me laugh and buying a Lana shirt with me at Hot Topic. Thank you Herzie for your smiles and your solace. Thank you Lane for serving Vivienne Westwood at the funeral and setting a new standard in fashion and coolness. And thank you Aunt Heidi, for helping to raise us, and for being so strong, and for speaking the truth and standing up bravely against this horrific crime.

❤️

💙💙💙